After a first winter, in the 1980s interest in Artificial Intelligence was rekindled. In addition to the increase in funds and investments in research projects on AI, there was a rediscovery of knowledge-based systems (originally developed by Edward Feigenbaum in 1965), which went against the trend with used systems that solved a problem by “reasoning” through a series of logical propositions. Instead, expert systems imitated the decision-making process of a human expert, and were widely used in industries.

Despite the clamor around expert systems, the results were not as expected and the general interest declined as expectations could not be met. In the late 1980s, major AI research financiers such as DARPA decided to stop investing in order to focus on other technologies with better prospects in the short term.

This other setback led – from 1987 to 1993 – to a second winter of Artificial Intelligence. In the early 1990s, the term Artificial Intelligence became almost taboo, and was often replaced by other terminologies such as “advanced computing”.

However, despite fewer government investments and a climate of less public interest, the end of the millennium was marked by a series of advances that gradually revolutionized the field of AI.

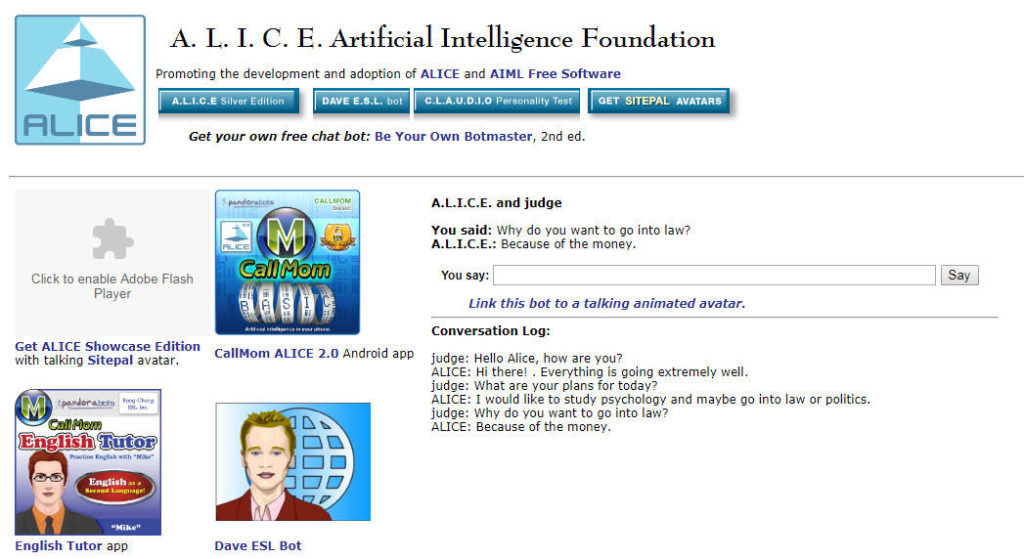

Interact with A.L.I.C.E.

By the early 1990s, many programmers tried to develop software that could approach, and possibly pass, the Turing Test. In 1990, the Loebner Prize was established, an annual Artificial Intelligence competition that awarded the bot whose behavior was more similar to human thought.

In 1995 computer scientist Richard Wallace developed the chatbot A.L.I.C.E (Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity), inspired by Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA program. ALICE, like ELIZA, had enough basic knowledge to hold a conversation with a human.

What differentiated ALICE from ELIZA was the addition of a sample data collection of natural language, made possible by the advent of the Web, which allowed to elaborate the meaning of a phrase through specific keywords or terms, avoiding in-depth and complex analyses.

This approach made it possible to subdivide sentences by category in such a way as to satisfy the most common questions asked in a conversation. In any case, the use was extremely restricted and efficient only in those cases where there was a very limited dialogue.

Although ALICE is one of the most successful chatbots ever created and has won the Loebner Prize three times (2000, 2001 and 2004), it never managed to pass the Turing test.

Deep Blue vs Kasparov: the game that changed history

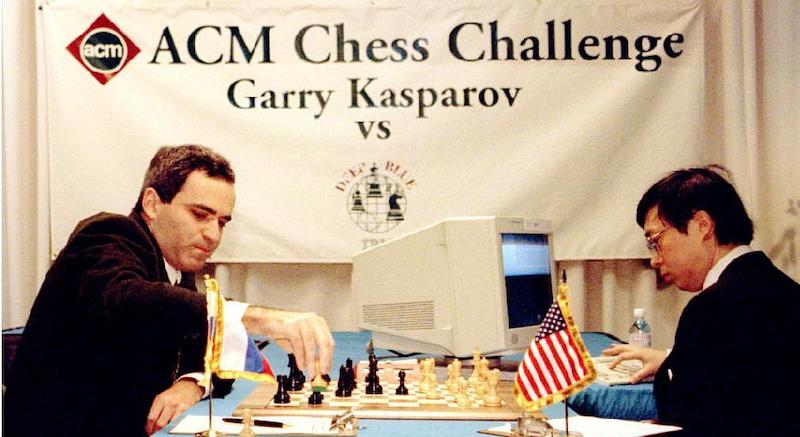

In 1997, a calculator named Deep Blue won a chess game – on a regular basis – against reigning world champion Garry Kasparov, known for winning the title at just 22 years old.

The original project was called Chiptest, a computer created in 1985 to play chess by Chinese computer scientist Feng-Hsiung Hsu with the help of Canadian Murray Campbell. Hsu and Campbell were hired in 1989 by IBM Research to carry out the project: the famous computer Deep Blue was born (a merger of the initial name of the project “Deep Thought” and “Big Blue”, the nickname of IBM).

Deep Blue was not an ordinary electronic computer, but a supercomputer capable of processing and analyzing 200 million moves per second. Taking advantage of extensive documentation of chess games played, it was able to store thousands of different openings and closures. His computing skills allowed him to predict and evaluate possible moves and strategies with enormous anticipation, allowing him to respond dynamically to moves made by an opponent.

The first match between Kasparov and Deep Blue took place in 1996 in Philadelphia. The victory was won by the Russian chess player despite the computer managed to win two games (it was the first time a world champion lost a game played against a computer with regulatory time limits).

Hsu and Murray didn’t lose heart: they integrated into Deep Blue the experience gained in the previous match against Kasparov and summoned some chess champions who could teach the computer new tactics and put into his memory other libraries of openings and closures.

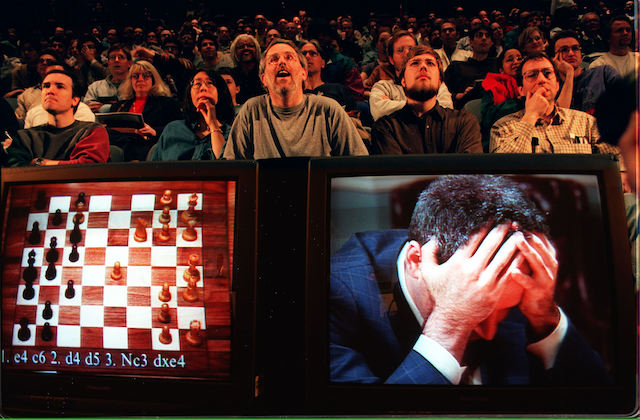

The rematch was not long in coming, and the following year a deeply updated Deep Blue (unofficially nicknamed “Deeper Blue”) challenged Kasparov to New York. This time Deep Blue managed to overcome the world champion, winning a resounding victory.

After losing the match, Kasparov accused IBM of flanking Deep Blue, who was not in front of the board but placed in an IBM office, some skilled human players. Kasparov also asked to be able to review computer records and arrange a rematch. But, IBM declined both requests and withdrew Deep Blue.

Despite these and other controversies regarding the relationship between humans and machines and the supremacy of one over the other, this revolutionary event paved the way for a wide range of possible applications of Artificial Intelligence, to address complex problems in other fields using in-depth knowledge.

Dragon Naturallyspeaking and Kismet

Another step forward in interpreting natural language was made by Dragon Systems of Newton, Massachusetts. The company, founded in 1982 with the aim of releasing products focused on their prototype speech recognition, in 1997 released Naturallyspeaking 1.0.

This speech recognition software, which included the standard natural language, was the first inexpensive computer dictation system. It was later implemented on Windows.

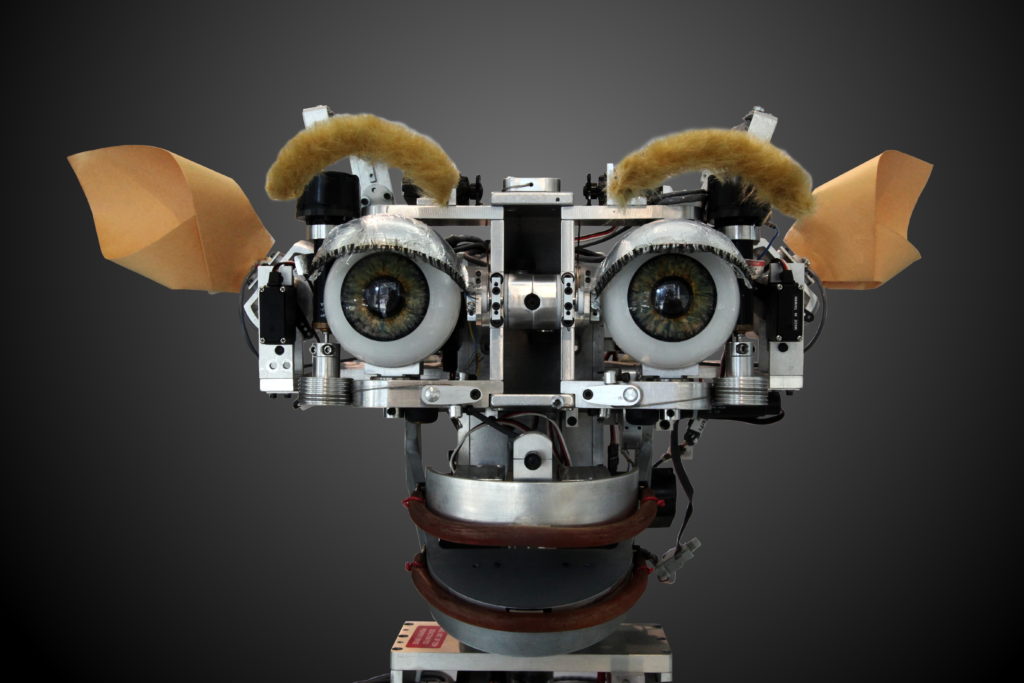

Even reading human emotions seemed a breeze thanks to Artificial Intelligence. Kismet is an expressive robotic creature – a head for precision – made in 1998 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by Dr Cynthia Breazeal as an experiment in affective computing.

This machine was able to interact properly with humans, thanks to input devices that gave it auditory, visual and proprioceptive abilities. Kismet recognized and simulated emotions through various facial expressions, vocalizations and movements. Facial expressions were created through the movements of the ears, eyebrows, eyelids, lips, jaw and head.

At the end of the millennium, it seemed that there was no problem that machines could not handle…

You can find more articles on history of Artificial Intelligence under the category AIhistory or at this link.